A cold day

As you might remember, I mentioned in a previous blog post that my grandfather’s brother, Jan Ingemar Holmquist, flew for the Swedish Air Force during the cold war. Unfortunately, 1952 on December 11th he collided with another airplane during an exercise flight with a Vampire J28. Both planes involved in the collision plunged into the ground. So how did it actually go for the two pilots? What happened that day?

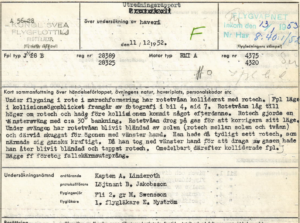

Thanks to Hans Brandt, previous fighter pilot at F7 Såtenäs, and Göran Jacobsson, expert on Swedish air force history, I have got my hands on the commission report.

So, let’s make a trip back to 1952, December 11th, a day that in many ways came to reflect the harsh conditions and coldness of the ongoing war. The following story is a reconstruction of the events as expressed in the commission report dated December 13th, 1953.

In the early Cold War, Sweden began sending out its young pilots on increasingly risky and advanced low-flying exercises. This was considered necessary as the threat from foreign powers felt significant at the time. Sweden was caught in the middle of a war characterized by distrust and tensions between the communist East and the capitalist West. As the preparations for a potential invasion increased, more and more Swedish pilots payed with their lives.

The pride and greed that grew forth with soldiers in service often overthrew the fear and concern that naturally arise from conflicts. These attributes could especially be found in pilots. They were often brave, filled with honor and they rarely backed away from challenges. According to flight physician E. Nyström, the two Swedish pilots, Jan Holmquist and Ingvar Lindeberg fulfilled these attributes despite of their low ages. According to evaluations they often showed both courage, will and determination during flight sessions.

It was a chilly day, the 11th of December 1952 at the royal Airforce F8 just outside of Stockholm. It was soon time for Holmquist and Lindeberg to practice flying. Both looked forward to getting up in the air again. Holmquist, 21 years old had around 200 flight hours, and Lindeberg with his 20 years came close with his 192 h. The day was clear and cold, the visibility under the clouds was around 8 km, and over the clouds the visibility was very good at around 50 kilometers. The wind blew cold with its 8-10 meters per second. It was a good day to practice flying and both Holmquist and Lindeberg had flown under significantly worse conditions.

They got ready and boarded the two planes of the model Vampire J28. They were both well-off as they moved out to the runway. The control tower gave them the green light to start their exercise flight and one after each other, they lifted, unaware of the fact that neither of the two aircrafts would ever return home again.

Holmquist could feel how the G force pushed him down while he aimed for the clouds. A few minutes into the flight, the two pilots were stable at an altitude of about 2500 metres in marsch-formation, Holmquist just before Lindeberg.The engine of the type RM1A gave both the aircraft a maximum speed of approximately 700 km/h.

The air traffic management had closely monitored the development within the European military aircraft industry, and in 1944 it was clear that the propeller era was over. In the autumn of 1945, a project named “JxR” was started, which would later result in the SAAB J29 Tunnan aircraft. During the same time Vampire aircrafts were imported from the British company “de Havilland” to enable pilot-training, and to bridge a stable transition to the new jet age. Sweden and British RAF (Royal Air Force) thus became among the first air force in the world to fly the Vampire aircrafts. The aircraft later received the Swedish name J28, and the earlier versions, J28A, were to be used mainly for pilot training.

Holmquist turned left with a 30 degree baking and Lindeberg suddenly ended up slightly behind Holmquist, thus pulling on gas to keep the distance constant. In the same moment, he was dazzled by the sun, of which he released the gas and shaded the sun with his left hand. Suddenly, Holmquist’s aircraft approached Lindeberg’s very quickly and Lindberg took down his arm and tried to slow down, but it was too late. The two aircrafts collided. At the moment of collision, the right tail of Lindeberg’s aircraft was torn off when hitting Holmquist’s aircraft, and as a result Lindeberg’s aircraft lost all its ability to stay airborne. The severely battered aircraft did no longer respond to rudder maneuvers. Lindeberg therefore took the very fast decision to jump. He untapped himself from the aircraft, opened the hatch and got sucked out of the airplane as a result of the high velocity. The spite of being hit in the face by his harness and the fact that he hit his shoulder in the hatch opening, he managed to stay conscious enough to pull out his parachute.

Further up in the sky, Holmquist had felt the collision underneath his airplane, and had in the same moment seen Lindeberg’s aircraft plunge uncontrollable into the clouds. At about 600 km/h Holmquist went down to an altitude of 750 meters. The rudder bounced from side to side and his aircraft started to spin out of control. The instruments were no longer readable. Holmquist tried his best to control the airplane, but failed. There was only one thing left to do, to leave the aircraft. He loosened himself from his harness, uncoupled his oxygen and radio, loosened the hatch and tried to climb out. Unfortunately, he was thrown back in the aircraft, giving him the impression that his parachute was stuck. He eventually put both his hands behind the parachute and got out. In the next second he pulled out his parachute. At the moment of release, Holmquist was so close to the ground that he did not feel the difference between the trigger shock from the parachute and hitting the ground. In other words, he had pulled out the parachute just in time.

A few kilometers from there Lindeberg had landed safely and moved to a nearby farm to contact F8. Just as Lindeberg, Holmquist managed without any injuries.

The story ended happily as both pilots survived. Jan is today 85 years old and he finished his career as a commercial pilot for SAS. Ingvar Lindeberg is also alive today at age of 84. Short after the accident Jan decided to propose to his girlfriend, Ann-Charlott, and you might guess what she answered. Jan Ingemar Holmquist and Ann-Charlott Holmquist is still married today.

A cold day with a sunny end!